|

This post is free advice for grad students: just say no. As you progress through grad school, you'll probably be asked to do more and more stuff. A committee here, a book chapter there, and a million meetings and emails everywhere. In the interest of your sanity, learn to say no. A lot.

This is something I've failed to do over the past 4 years, and I've often paid the price for it. And I've said yes to stuff a lot of the time because it was nice to be asked. "Wow," I thought, "people want to work with me!" It's flattering. But you should only answer yes to these requests if it checks two boxes: Does this help you graduate in a timely manner? Does it help you get a job? Lest I be accused of advising grad students to do the least amount of work possible, this is not what I'm suggesting. My own biases suggest that success often means doing more than just your coursework, graduate assistantship, and dissertation. But you have to be selective. If you want to go into academia, being the grad student representative on a selection committee is probably a great idea. If you want to go into the policy world then writing that monograph for a think tank is probably a great idea. If you have a family then that job outside of school is probably necessary. Here's what you should probably say no to. Conference papers that aren't written as part of your fellowship or dissertation. Probably most book chapters and encyclopedia entries. Book projects that aren't your dissertation. Be selective about guest lectures, article reviews, workshops, and requests for random writing projects. You will probably have to make a list ready in your head of the people you will always say yes to no matter the circumstances. Everything else needs to be weighed carefully - your default should be no, unless a solid case can be made that a new commitment is worth your limited time. There is no one answer for every person - we all have different goals and needs, but have a mental rubric to help you navigate these decisions. Time is a scarce commodity that becomes more dear during grad school. Over-extending yourself is easy to do and it can make it hard to complete the things that you absolutely have to get done. Like your dissertation.* *In case any of my committee members read this, I'm still on schedule!

0 Comments

I have new research out with the U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute that looks at operations in Kosovo in 1999 to 2000. The purpose of this series is to provide case studies for professional military education, specifically to examine how conditions and politics drive operational design. It then assesses how the design is executed and what that meant for the long-term stability of the target state.

It was an interesting exercise to go through, if a bit depressing. Kosovo is generally considered a relative success in the stability operations world, but that was in spite of the planning and not because of it. The whole story does not cast senior military leaders at the time in a good light and any successes that could be claimed were almost entirely due to experienced (recently in Bosnia) leaders on the ground making it up as they went along. Even more depressing, every lesson that could have been learned here was completely forgotten in 2003. Or ignored, rather. But that seems to be an institutional habit in the U.S. Army. This semester I'm teaching International Security Politics at the Elliott School. It's a survey course and one of the sessions is dedicated to classical texts. If you know me at all, you know that I'm going to spend most of that session on Clausewitz. As I was preparing for class this week, I was rereading the first chapter of On War - probably a little more closely than normal - when I noticed that this chapter discusses each of the causes of war under a bargaining model.

For those of you who aren't political scientists, the bargaining model suggests that in any conflict there is some overlapping area of where the two sides could avoid war. James Fearon's listed three cases where war occurs anyway under this model: private information and incentives to misrepresent, commitment problems, and issue indivisibilities. And there in Book I, Chapter One, written 160 years earlier, are all three of these reasons for why war occurs or doesn't. Section 18 on imperfect knowledge is all about private information. Sections 13 and 16 cover commitment problems. To a certain extent, Section 15 and "polarity" closely resemble the ideas in issue indivisibility.* Certainly, Clausewitz is taking a different approach than Fearon with his focus on the suspension of military action, but the concepts are highly related. Because I love when Clausewitz relates to my primary work, I tweeted about this. Lindsay Cohn at the Naval War College has some related research coming out soon and also pointed me to Dan Reiter's references to Clausewitz in his "Exploring the Bargaining Model of War." Fun stuff. * Polarity is potentially not quite the same meaning as indivisibility, but Clausewitz never wrote the chapter he promised on the topic. But the stuff before getting to the attack/defense dialectic hints at a synonymous meaning at the war level that could be extrapolated to the political level. This discussion probably warrants significant treatment on its own with Aron's commentary as a good starting point. Funnily enough, Fearon almost equally hand-waves issue indivisibility. It's been nearly two months since my last post. Since then I've been busy with work and research, including grant and book proposals, regular research, and kids stuff. And as of two weeks ago, I'm adjuncting for the first time starting in January, so I had a syllabus to throw together.

But the big event was last week when I passed my dissertation proposal defense. I was going to make this post about my dissertation itself, but thought rather to make it about the prospectus process. Nothing like "wisdom" from someone who just did something, right? Like learning military strategy from a private fresh out of basic training. In spite of this I thought I'd write about it because it was for me, by far, the most stressful time I've had in grad school yet. Coursework and comps can be stressful, and they are barriers to continuing to many people, but I've always managed to keep these sorts of things in perspective: they were never close to the hardest things I've done in my life. This was something new and unusual, with huge impact, and I had no idea what to expect going into it. But for some reason, my proposal defense really got to me. I wasn't worried about washing out or anything, but unlike comps it wasn't a hoop to jump through, a right of passage. It is an important step in the dissertation process, which can (from my perspective) define the initial stages of my career. So getting it right is important, which is hard when you're going into a meeting that feels like a broadside against your work. Meanwhile, even though your committee is there to help, this is when the training wheels really start to come off and decisions are ultimately up to you. I don't know about other schools, but I didn't have prior proposals to use as examples - it seems these are mostly unique events, each one. I had an idea of what I want to work on, where it fits in the field, and how to get there, but not how this high impact process works. And it's the first time you're really on your own in grad school. I've heard about the lonely road that is a dissertation, and the proposal process are those hard first miles of it. I was a ball of nerves for the whole week before. For the first time since maybe my first year, I asked a friend/mentor to talk about it and that was the best decision I made in preparing for the defense: everyone goes through this, it seems. Knowing that made it easier to handle. That's not to say the defense itself was easy. My committee had a lot to say, and like most of you I'm guess you don't like hearing about the obvious things you missed. It's embarrassing. But. It was probably the most useful hour and a quarter I've had in grad school, getting pointed, detailed feedback on my research plan from people invested in making sure I succeed. There's a long road ahead on actually getting this dissertation done, and this was a difficult milestone along the way. Going into it, I questioned the point of making it a formal event, but now that I'm through it, I'm glad that it's actually kind of a big deal. It increases the sense of accomplishment, even though the outcome was more work. But for those of you going through this in the future: this is hard. It's stressful. It's probably unlike anything you've done before. And (from my small-n convenience sample) everyone seems to go through the same thing. But there's a method to the madness, and it's really worthwhile. Know that you're not alone, prepare as best you can, and call a friend. Some of you may have seen that as of a few weeks ago that I had been looking for new work as the company I was with ran into some hard times. Since then I've joined War on the Rocks part-time as our member engagement director. The most public-facing part of that is that I now host WOTR's members-only podcast The WarCast. If you like to hear me talk to interesting people, now would be a good time to become a member.

This is an ideal arrangement for me at the moment. First, because now that I'm through my comps I can focus on my dissertation better. Second, I can jump on individual research projects as they come up instead of chasing things that I don't really have any interest in. The coming weeks will be all dissertation proposal, all the time that I'm not working. In other news, my article with Joe Young on American anti-ISIS foreign fighters is out and the link on my research page provides free copies for the first 50 clicks. David Ucko, at the National Defense University, and I wrote a critique of a recent International Security article on counterinsurgency. We weren't fans of the piece for a number of reasons, and I hope you give it a read (as well as the original piece for context - I'm not linking because it's behind a paywall, but it's easily found if you have access to IS). ISSF was an ideal outlet for our critique as the journal's correspondence section limits word count to a significant degree.

I don't write much on COIN these days, and I think these were my last pieces on the topic. The entire endeavor had become futile and there didn't seem much point. Too much of the debate, such as it remains, still sits in the pro- and anti-COIN camps like it's still 2009. But reality is much more complex than this, in understanding what our doctrine says, what the scholarship says, and what actually happened on the ground. Indeed, the COIN debate seems to still be entirely too self-reflective, instead of incorporating other fields of study. Like the literatures on civil war, state repression, state-building, or even selectorate theory. Instead, it's the same citations (Galula, Nagl, Gentile, etc) over and over again. It's very frustrating that the conversation goes in circles instead of progressing. Which is all to say this was an interesting piece to co-write. But it also doesn't mean that I'm stepping back into the conversation. Or rather, I'm moving on to a different conversation: trying to understand the nuances of COIN -- as espoused by doctrine as well as viewed by scholars -- and examining new research for it's contribution to a progressing dialogue. Like my last COIN pieces 4 years ago, I suspect some perspective on what's been written is more useful than new theories based on broad brushes. After a short vacation in July and some travel during August, I'm finally getting back into my normal routine. As I'm trying to wrap up a few projects (still), get a couple of new ones started, prepare for a comp, and wrangle my prospectus into shape, I'm trying to identify where I'm losing the most time during projects.

I realize a lot of people have a hard time getting projects started. I'm definitely one of them. For me, the time between a thought that I think is worth writing about and when I start putting ideas down on paper is entirely too long. I have to think and think about it. Solve a bunch of the problems in my head. Take copious notes (usually on paper). Read and read and read and read. And then I start putting it down, with the outline and form already figured out. This presents two problems. First, I need to trust my knowledge of the literature more than I do. I need to just start writing the big picture stuff down and then fill in the details - or change it if the evidence suggests I'm wrong. Second, I suspect I use it as a delaying tactic. "Oh, I'm not going to start that yet, because I have this huge hurdle I need to figure out." Whereas writing it down and forcing myself to deal with it head-on would probably save me more time and increase my productivity. Anyway, there is a very busy year ahead of me. I've managed thus far, but as my workload gets worse and worse, I'll be looking at (and sharing!) ways to make my research more efficient. Now to follow through.... Speaking of which, I told a few of you that I'd write about some odds and ends. It's on my list. I guess I should probably just start typing them and stop thinking about them. Over the next few weeks I'll be editing and putting the (hopefully) final touches on three major bits of research, some of which I've been working on for over 2 years. Final in the sense of the respective stages for each (R&R, monograph, initial submission). But certainly I'm nearer the end of these projects than their beginnings.

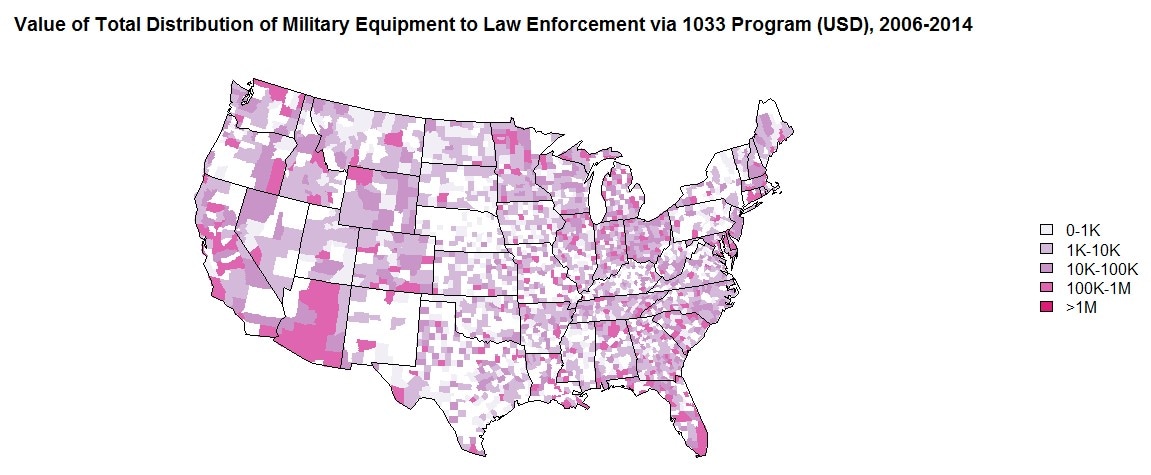

Meanwhile, I'm starting 2 projects in the near term (and maybe a third). Sure, I've been thinking about them and have been kicking around ideas for a few months, but other than my dissertation I don't have any projects begun, never mind towards the middle range of completion. There are a number of reasons for this, including trying to get work done of the three projects mentioned above, ending coursework, and preparing for comps. I'm not sure this matters or not, but I'd like to have a project or two closer to ready for publication with a good push of effort. If I find I need some more pubs as I hit the job market in about a year, I might be too far to get one at least submitted to a journal. I'm also a bit concerned that I've been putting off starting these other projects until I've cleared my plate. I don't like this clustering approach, not least because it means I'm in the hard middle parts of all of my projects at the same time. It's a mental drain, as much as kicking all your projects out the door at the same time feels great. I'd like to balance more, if only for my emotional needs. Over the next year or so, one of my professional foci will be to better manage my research so that I'm tackling all that can and moving them all forward, irrespective of where I am in the course of each project. I've been following the advice of Raul Pacheco-Vega at CIDE (such as this example). I'm sure there are others and would appreciate useful links. I've spent part of today teaching myself how to plot data in R, mainly using the maps package. I found a number of ways of doing it, but this from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute was the best guide that I came across to get started (you can see I kept their color scheme). I still have tons to learn about this at the basic level, including getting the aesthetics right. Some of you are probably literally pros at this and may chuckle at my adorable mapping attempts, but hey: I'm new to this.

About the data here... This is part of a project I've been working on for some time that is getting closer to done and that I presented at MPSA this year (I suspect one or two of you may have been at that panel). I've been working quite a bit on the distribution of military equipment to state and county law enforcement agencies, specifically through the 1033 Program. In the aftermath of the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO in 2014, the New York Times obtained the Defense Logistics Agency's list of equipment transferred under the 1033 Program. The problem with most of the plots based on that data is that it does not account for the fact that most of the equipment in that dataset isn't military equipment or it's a very specific subset of military equipment. The full data contains lots of desks, computers, exercise equipment, what have you in the way of non-military equipment, and other types of military equipment beyond what the NYT offers on the map in the link. I've gone through and coded every line (over 200,000 of them) of that data as military or not-military equipment. For the former, I've categorized further to test a number of hypotheses about why agencies ask for certain types and what are the outcomes of that on crime. The plot above simply sums the value of military equipment transferred during the time period the dataset covers, by county. Anyway, I'm hoping to wrap up the model specifications and estimations, address some feedback, and get it off to a journal soon. This was fun and I'm going to overlay some other stuff onto it, so hopefully it will be useful as well. Back to reading up on dynamic causal models of panel data. [Author's Note: I had a longer post on this, but Weebly decided to delete all but the first sentence when I tried to post it. So it's mostly links. Thanks, Weebly.]

Daniel Byman and Will McCants have an interesting piece in The Washington Quarterly on how to avoid 'forever wars.' They offer some red lines on when to intervene against terrorist groups to add some order to how we engage them. It's good advice even if implementation might get a bit sticky. Any time I read about safe havens I return to an article by Elizabeth Arsenault and Tricia Bacon that is truly excellent. They provide a typology of safe havens and policy advice for each quadrant of the typology (huzzah for two-by-twos!). It's my favorite piece on the topic and as it focuses on how to work with host governments. You should read it. |

AboutHave you ever wanted to follow my research in (not-quite) real time? You've come to the right place. Archives

June 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed